The birth of the Los Angeles music business essentially started way back in the early 1940s when Capitol Records was started. Not many would have bet on the little label—created above a record store—to compete with the Big 3 of Columbia, RCA-Victor, and Decca, but it quickly became a player with the signings of T-Bone Walker and Nat King Cole and by the 1950s was “resurrecting the washed-up career of Frank Sinatra.”

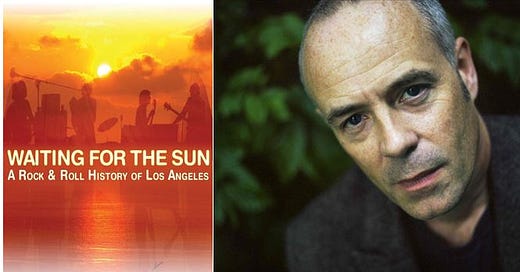

I’m reading about these heady early days of L.A. music in Waiting for the Sun: A Rock ‘n’ Roll History of Los Angeles, published in 2009 by Barney Hoskyns (pictured). With the value of the label in 1954 shooting up to $8.5 million (or about $100 million in today’s dollars), it was able to purchase the iconic “Stack O’ Records” building. By the end of the 50s, record labels were dotted all the way down Sunset Avenue, where meat-company employee Sonny Bono would regularly drop his recordings off in hopes of landing a deal.

Herb Alpert and Lou Adler (as well as the “chinless, asthmatic” Phil Spector) were a couple of the independent record producers scooping kids off the street before the big labels and Capitol could get to them. They grabbed Jan and Dean literally off the beach, where they were playing volleyball, and quickly cut some records and made them stars. Frank Zappa turned in some early recordings but labels said the guitars were too distorted to release. But that didn’t stop the course of rock ‘n’ roll, because Spector set up shop in a seedy studio in Santa Monica and perfected his “Wall of Sound” production style, with Bono as his sometimes assistant who had “his nose up Phil’s ass a mile.”

But Spector or Jan and Dean weren’t really enough to make the record honchos back in New York take California’s music scene seriously. It took the entrance of Brian Wilson and his surf pop to get them to finally take notice. Surfing had existed since the beginning of the century, but fiberglass-encased boards were a new thing at the start of the 60s and there were now about 30,000 surfers at Southern California beaches on weekends. It wasn’t long before Gore Vidal’s novel Myra Breckinridge was becoming true: “In a single generation, stern New England Protestants, grim Iowans, and keen New York Jews have become entirely Tahitianized by that dead ocean with its sweet miasmic climate in which thoughts become dreams.” Much like Hollywood had done through movies, surf music was now helping rock ‘n’ roll and L.A. define and redefine itself for a new generation.

One of the many great ironies of Wilson becoming the chosen one to land L.A. rock on the map was that he was an “all-American misfit” and he and his brothers were “pure white trash, West Coast hillbillies.” Brian couldn’t relate to girls and didn’t like the ocean. Years later, he appeared on Saturday Night Live in a sketch with John Belushi arresting him for never having surfed and “it was excruciating to watch the nervous, overweight genius being forced into the Pacific … The fact remains that The Beach Boys were as much an illusion as anything churned out by Hollywood.”

Hoskyns’ book is filled with outrageous language like this. His writing would be unbearable if it weren’t so entertaining and also if he didn’t make similarly large claims from the other side of the see-saw such as Wilson’s melodic genius being “almost unparalleled in the history of rock” or that The Beach Boys “were the first garage band.” Part of the good fortune of the Beach Boys was that Nik Venet—a 21-year-old producer at Capitol in a city of producers who were routinely much older—got ahold of them and helped catapult them to stardom, and L.A. music was really on the map.

Brian holed up in the studio for “work, work, work” while all the other Beach Boys “made hay in the California sun, exploiting the teen-girl mania that greeted them everywhere they went, Dennis Wilson picking fights with boyfriends of fans, David Marks caught VD, and even dumpy little Carl Wilson lost his virginity.” Soon The Beatles’ arrival would harken the beginning of the end for the surf-pop craze, although the spirit lives on, with pop-culture artifacts such as Tom Wolfe’s 1968 collection The Pump House Gang, Baywatch, and Beverly Hills, 90210. Of course, everything in rock music is borrowed, and all of L.A.’s surf music and culture owes a great debt to Hawaii, a fact most people from Southern California are quick to sweep under the rug.

Meanwhile, the white kids’ “endless summer” of 1959 to 1965 “was experienced by Blacks as a winter of discontent.” Thirty percent of the Watts neighborhood was unemployed. And “once rock ‘n’ roll had been co-opted by white teenagers, the music industry forgot about Black performers.” There were some records made by Black people in L.A. during this period (although amazingly not many) and Sam Cooke was building his own little empire of labels from 1960 on. But when he was shot down in 1964 in what looked like a sex-hookup setup at a fleabag motel on South Figueroa Street, “with him died most of the hopes for Black music in L.A.”