I’ve religiously read The New Yorker ever since I was an undergrad literature major. At that time, I was drawn to the fiction in every issue but I’ve since kept returning for the razor-sharp political commentary, the unmatched investigative reporting (and exceptional editing, which needs to be mentioned in an era of seriously diminished fact checking and overwhelming misinformation), and of course the cartoons.

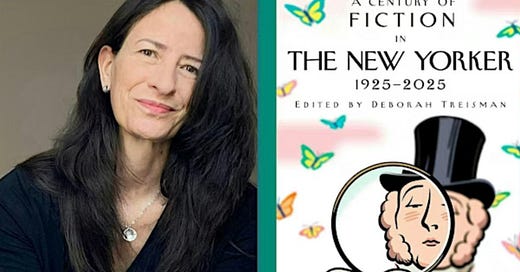

Taking me back to my fiction roots with the weekly magazine is a new tome titled A Century of Fiction in The New Yorker: 1925-2025. In the introduction, editor Deborah Treisman (pictured) gives a little background:

Harold Ross was the first editor and he mostly published fiction that did not particularly distinguish itself. The stories showed promise, but they were mostly “what we’d now call sketches—each a pithy short scene, bound to one setting, that ends with a punchline of sorts” in which the nearly always male protagonist “confronts a new reality. In the 1930s, plot was frowned upon. Parable, prophecy, fable, fantasy, satire, burlesque, parody, nonsense tales were omitted.”

In the 1940s, a lot of the writers also worked in Hollywood and dialogue was the thing. These stories were mostly morality tales told with detachment and despair.

The 1950s saw stories retreating from war and into domesticity. Up through this time, there were no labels on the magazine’s articles or in the table of contents, so readers never knew if they were getting fiction, memoir, reporting, or criticism. “One had to simply figure it out as one read.” Writers of other nationalities were rare also until about the late 50s.

Even up through the 1980s, “the magazine eschewed vulgarity, profanity, and sexual imagery.” “Fuck” didn’t appear until 1985 and “pussy” until 1993. Stories themselves had evolved into “full-blown narratives, almost mini novels.”

Out of 13,000 pieces of fiction published in the magazine over 100 years, the anthology picks 78 to highlight. It starts with these three stories …

“Life Cycle of a Literary Genius,” by E.B. White (1926) takes about a minute to read and tells the life story of a person who goes from a boy to a man, marking that growth process with each of his publishing milestones. The man dies and it even begins telling his illegitimate son’s story of writing the great American novel. It may not be as great as Charlotte’s Web—which White wouldn’t publish until 1952 —but it does show how brilliant The New Yorker was set to become. 5 out of 5 stars

“Over the River and Through the Wood” by John O’Hara (1934) presents the meanderings of an old man named Mr. Winfield who takes a car ride with his granddaughter and two of her friends. Nothing much happens in the course of the story by O’Hara—a literal giant in the first half of The New Yorker’s existence but a bit of a fading thought at this point—until the end when he accidentally sees one of the girls nearly naked. He knows his life is over at that point because others will see him as a doddering senile old man. I’m not really sure why this is included in the collection, but it’s luckily only about a 15-minute read. 3 out of 5 stars

“The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” by James Thurber (1939) is one I’ve read many times and, of course, it could never get old. One of the best short stories ever, it tells the tale of an afternoon in the life of Mitty, whose wife is getting her hair done and instructs him to go get overshoes and doggie biscuits and meet her later at a hotel. He nearly forgets both incidental items because he’s too busy daydreaming that he’s on trial, that he’s a military bomber, and that finally he is having his last cigarette before the firing squad turns towards him. It’s a wonderful reminder that the mind and the imagination are worth revisiting time and time again, even if you’re stuck doing the most mundane errands possible. In the year of The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind, Mitty is another reminder that there was something special in the air in 1939. 5 out of 5 stars